The State Within

The British are coming! / A terrorist bombs the U.S., setting off a cunning game of cat and mouse between allies in a masterfully rendered BBC production

The State Within: Drama. Part 1, 6 and 9 p.m. Saturday. Part 2, 6 and 9 p.m. Sunday. Part 3, 6 and 9 p.m. Feb. 24. BBC America.

For all the good-time Charlieness of “24” — the implausible accounts of terrorism on U.S. soil and the superhero who is Jack Bauer saving our Yankee backsides at every thrilling, explosive turn — it’s also nice to come in from the comedy once in a while and appreciate a smart thriller that tackles similar issues with real intelligence, superb writing and standout acting. For that, we can thank the Brits once again.

A new three-part, nearly six-hour miniseries called “The State Within” begins Saturday on BBC America, and it’s a cleverly crafted, ingenious thriller with only scant moments of implausibility. Most of it has the unmistakable imprint of a smart premise beautifully executed.

“The State Within” is both startling and intriguing from the opening minutes and sets a hook we don’t often see on American television because the point of view is not ours. A British national — a Muslim — sets off a bomb on U.S. soil, immediately fraying diplomatic relations between the two countries. That is just an inkling of what’s to come, as “The State Within” wanders into Florida, where an ex-British soldier is on Death Row, then weaves in a rogue Central Asian country, American military supply corporations and perhaps some high jinks within the U. S. government. One of the surprisingly welcome aspects of “The State Within” is that it’s complicated and hard to follow. It requires some focus and gives no immediate, path-specific indications of where it’s going to go. In short, you’re left guessing a lot and guessing wrong.

Jason Isaacs, an exceptionally good actor best known on these shores for his acclaimed work in Showtime’s “Brotherhood,” plays British Ambassador Sir Mark Brydon, a rising politician who many in his home country believe is destined to be prime minister at some point. He’s blunt, Brit tactful and not afraid to roll up his sleeves and get physical. It’s a compelling combination that makes him instantly likable and keeps your eyes glued to him. But Brydon suddenly has a lot of woes. There’s jealousy in his office and the Americans — in the form of U.S. Secretary of Defense Lynne Warner (Sharon Gless, who aggressively channels Madeleine Albright) — are extremely annoyed at the British for letting one of their “terrorists” make a mess of Washington, D.C. The governor of Virginia declares that British Muslims in the country can be detained without charge, which leads to many of them rushing to the British Embassy.

What’s unique about “The State Within” is that all of the issues currently at play in England are factors in the story, even though it’s set in United States. For example, as the hawkish defense secretary, Gless’ Warner character gets to lecture Brydon on how his country has, for too long, let a growing number of British nationals — namely Muslims — get entrenched in his country. (The July 2005 bombings that rocked Britain’s transit system led to a crackdown on “radical Islamic activists” inside the country, many of them homegrown.) The brief Virginia incident allows the writers to posit how the Americans might handle the situation.

Also at play is this notion: Being America’s closest ally essentially makes the Brits and, in particular, the prime minister appear to be following whatever orders the U.S. government dictates. The blustery Warner leans on Brydon quickly, but he proves a worthy adversary, conveniently extolling from her a public show of support she hadn’t been interested in granting. Now with their countries linked in solidarity to find out which terrorists were behind the bombing, Brydon comes under increasing pressure as the Yanks learn how deeply the British are involved (at fault?), and through a myriad of twists, Brydon is caught in the middle.

There’s a taut complexity that writers Lizzie Mickery and Daniel Percival never let slack in the entire miniseries. While “The State Within” isn’t afraid to construct some “24”-worthy scenarios of homegrown deception and government duplicity, the execution of these audacious premises is more intelligent. For example, the writers set off a series of random events that tie back to Brydon.

First, a disgraced former British ambassador, James Sinclair (Alex Jennings, who played Prince Charles in “The Queen”), is recruited by a Washington think-tank to harangue the Americans and the British about civil rights abuses taking place in the Central Asian republic of Tyrgyztan. Turns out that Brydon once had to make a difficult decision there in supporting the government of President Usman, now the fall guy for the torture and abuse ruining the country – and the corporations interested there, which stretch back to Washington and England.

Brydon had befriended Tyrgyztan rebel leader Eshan Borisvitch but was compelled for political reasons to prop up Usman, the kind of difficult political decision that often comes back to hurt one’s rising political ambitions.

Meanwhile, a plot is uncovered that suggests some off-the-grid British mercenaries are leaving Virginia and heading to Tyrgyztan to deliver nerve gas to President Usman’s regime. Why this is happening is unclear at the time, but it sure gets the Americans ever more annoyed at the British, as it reveals Usman to be a crazed dictator supported by both governments, and it might be, as Secretary of Defense Warner suggests, time to slap him down. As Brydon’s political career takes a seemingly unspinnable hit, he has a chance to put things right. Sinclair, himself political poison and a man Brydon is trying to avoid, has been in contact with Borisvitch, who’s in exile. The makings of a coup are shaping up.

What “The State Within” ultimately gets at is not merely the need to track down and stop terrorists on U.S. soil but the far more intriguing notion of special interests, hidden political motivations and who’s pulling the strings on the path to war — issues with all kinds of relevance to Iraq.

But seeing British writers construct their own theories and worries adds another layer, making it original, if not a bit far-fetched (at least in the beginning), for American viewers. It’s a bold gesture to suggest that Washington is crawling with Brits masterminding international chaos, but it’s thrilling nonetheless. And the way the miniseries weaves Brydon into everything is ingenious (and it allows Isaacs to be a triple threat of savvy diplomat, unexpected action hero and sexual attraction; this being an espionage thriller, there has to be sex).

“The State Within” manages to be pulse pounding as well as intelligent and complex, and takes very few missteps along the way. Even at six hours (the second installment airs a day later and the third on the following weekend), it’s not nearly enough. The ending is also something we never get on American television — and whether it leaves you thrilled or galled doesn’t detract at all from the journey there. [Tim Goodman]

Every Time You Look At Me

Director: Alrick Riley

Production Company: BBC

Producer: Ewan Marshall

Script: Lizzie Mickery

Photography: Dewald Aukema

Cast: Mat Fraser (Chris), Lisa Hammond (Nicky), Lindsey Coulson (Kath), Lorraine Pilkington (Michelle), John Woodvine (Roger), Stuart Laing (Steve), Jan Carey (Ann)

Two disabled people fall in love, but find themselves confronting their own prejudices as much as those of society around them.

It’s a familiar scene: a packed nightclub, two people’s eyes meet, one comes over to introduce himself… but in Lizzie Mickery’s drama (BBC, tx. 14/4/2004) Chris (Mat Fraser) then discovers that Nicky (Lisa Hammond) is only four foot one, and she in turn sees that his arms are only half the expected length thanks to the side-effects of the thalidomide drug that his mother took in pregnancy.

Given the confrontational persona that he’s shown through his career to date, it comes as little surprise that Mat Fraser’s first lead role in a feature-length television drama would be in something like Every Time You Look At Me, whose narrative constantly challenges not only its audience’s expectations but also those of its characters – not least Chris and Nicky themselves.

The line quoted in the title, “every time you look at me you see yourself”, sums up their dilemma. Having spent their lives trying to rise above their respective disabilities and integrate seamlessly into ‘normal’ society, they’re initially horrified by the prospect of them becoming a couple, and Chris is given a further test when, shortly after he proposes marriage to Nicky, her mother Kath (Lindsey Coulson) reveals that her daughter’s problems aren’t restricted to her height.

While the film occasionally resorts to sequences showing the obstacles Nicky and Chris face in their daily lives (notably when they check into the hotel independently, and finding that everything from the length of the chain connecting the pen to the reception desk to the height of the lift buttons conspires to thwart them), it’s otherwise notably matter-of-fact about disability. In particular, the scenes of physical love are shot with a tenderness and sensitivity that implicitly rebukes film-makers who have shied away from such material in the past.

Producer Ewan Marshall had previously tackled disability-related issues in three short BBC films from 2002, North Face (tx. 26/9), The Egg (tx. 2/10) and Urban Myth (tx. 3/10), the first and last of which featured Hammond and Fraser respectively. Given the chance to make a 90-minute feature, he commissioned Mickery’s script with them specifically in mind, and Fraser has claimed that this is the first television romantic drama to be based around two disabled lead performers. It was also the first BBC film to be shot on high-definition digital video, which produces a far more lustrous image than conventional video while retaining the advantages of electronic post-production. [Michael Brooke]

Adventures of the Soul

The Wire on BBC Radio 3

BBC Radio 3, 27 October 2012

“Sorry,” is one of the most overused words in British English. It is used to attract attention, as a synonym for the word “Pardon?”, and most obviously as a so-called apology if someone transgresses a particular social or behavioural code. If a person pushes past you while running for the train, they are likely to say “sorry,” as they knock you over; they are likely to use a similar phrase if they say something deliberately offensive. More often not they do not mean what they say: the term represents an insincere attempt to make things right.

This phrase provided the impetus for Lizzie Mickery’s ghost-story, in which Clare (Helen Bradbury) understands that something – or someone – has taken up residence in her house. No one believes her; not least her husband Tom (Lucas Smith), or the private detective Philip (John Hollingworth), whom she approaches in an attempt to solve the case. As is turns out, there is someone there, speaking to her during the night through the airwaves in a tone that forces her to listen. When she subsequently discovers that her dead father’s identity has been stolen, she immediately understands who the spirit is. The only way she can deal with it is find a way to communicate with him.

Using an excellent soundscape incorporating recordings by collector Raymond Cass, Melanie Harris’ production focused on the relationship between past and present: we all try to unmake the past (for example, by invoking the term “sorry,”) when it is physically impossible to do so. We should look into ourselves and find a way of solving this crisis, just like Dante recommends in The Divine Comedy – a text that was frequently alluded to during the production. Clare eventually understands this, and realizes at the same time that she has no further need of Philip’s services. He is a detective, concerned primarily with logical solutions to cases; what Clare discovers is that human beings have to find “illogical” (possibly “incorporeal”) ways of dealing with the past.

While the production contained some truly scary moments, it began as a Gaslight- like study in female suffering, and ended with Clare as the most emotionally self-contained character. I really enjoyed it.

Murders she wrote

The Guardian, Friday 27 August 2004

Lizzie Mickery writes some of the most gruesome drama for television. She tells Gareth McLean why she has no qualms about inflicting violence on her female characters…

Once, Lizzie Mickery tied a man to a hospital trolley and cut out his heart. She’s stabbed a librarian in the throat with a pair of scissors and suffocated an asthmatic in a giant bag of laundry. She also wrapped a man in bandages and buried him alive. He later died.

But Mickery does not reside in a hospital for the criminally insane, nor in a cave carpeted with human bones. She does write for television, however – a career that can end in institutionalisation or homicidal misanthropy, and sometimes both. As the writer of Messiahs I, II, and now III, Mickery is already au fait with murder: the classy serial-killer thrillers starring Ken Stott are synonymous with blood-spattered inventiveness and body counts that make John Webster look restrained. Even if, as Mickery says, “you don’t see as much as you think you do”, the Messiahs are still awash with suffering, both physical and psychological. They are, and make of this what you will, Event Television – opportunities for the whole family to sit round on a bank holiday and watch unsuspecting individuals have their throats slit at the opera or be barbecued to a blackened husk while hanging by a railway line.

Messiah III is no different. Those with a fear of hospitals, confined spaces or both, will be particularly freaked. And as in previous instalments, you can’t help but admire the killer’s resourcefulness, especially when it comes to his/her employment of an MRI scanner.

But the drama’s most frightening moments don’t involve any of the grand guignol thrills for which the franchise has become famed. Instead, it’s the threat of a more real violence directed towards DS Kate Beauchamp (Frances Grey) that provides the real chill. Held hostage during a prison riot, Kate finds herself not just a lone woman among a band of brutal men, but also a symbol of the power that’s imprisoned them. The prospect of gang rape is unavoidably intimated: Kate is passed between the men and has her mouth forced open with a phallic tool. She ends up offering herself to them with a pitiful, “Anything you want …” It’s a very upsetting scene.

Mickery, you will have gathered, has no compunction about inflicting harm on her female characters. “I suppose there would be specific things that would be worse if they happened to you because you’re female, but the situation in which Kate finds herself, is because she’s a police person. Maybe the audience will think it’s worse because she’s a woman, but I wrote her as I think any policewoman would like to be written – as somebody who goes in there to do a job. Why should she be left out of that just because she’s female? I think that Kate would say that that was the risk she was prepared to take.”

Mickery says that she is gender-blind in her writing; as a female writer she has no more responsibility to her female characters than a male writer does. “They are all characters to me. A lot of the best crime writers are women. If it was PD James or Elizabeth George, no one would think twice about it. So why is it that a woman writing television gets criticised?”

As detective drama goes, Messiah is at the more sophisticated end of the genre. Partly this is down to its hefty budget (£1.1m an hour) and strong central performances. But it’s also down to Mickery’s knack for tapping into common fears. Many of her murders involve being trapped or restrained, and who hasn’t had a nightmare about being buried alive? “In Messiah, things do hurt,” Mickery says. “Everybody suffers – the team, obviously the victims, even the killer. It isn’t one of those dramas where everything is lovely and fine after the killer is unmasked. The trauma endures.” Finally, Messiah makes sense. You can, if you’re so inclined, work out the logistics of the crimes; a fact of which Mickery is very proud. This separates it from, for example, the increasingly nonsensical, compulsively rubbish Waking the Dead.

It’s also good because Mickery is a good writer. She also wrote the superlative Sinners, BBC Northern Ireland’s drama about the Magdalen laundries; Every Time You Look at Me, BBC2’s love story about a disabled couple; and is co-writer of the upcoming Dirty War, a drama-documentary about the detonation of a dirty bomb in London. The latter was a departure for Mickery, who normally writes alone. “Dan Percival, the man who brought you Smallpox 2002, had the idea long before I was involved, but after I got sent the documentation he had, I had to be involved: I thought it was an extraordinary subject. It had to be absolutely correct for obvious reasons, and we had a research producer and two research assistants working on it. Then, when it was time to write it, we sat down side-by-side and started from the beginning. Although it is very dramatic and, I hope, very engaging, it is a drama-documentary based on rigidly correct information.”

Once a jobbing actress, Mickery appeared in Tenko (“I was last seen getting into a truck in Singapore”) and Juliet Bravo before getting a break after sending a script charmingly entitled Wankers’ Doom to London’s Bush theatre. That led to the production of other work, and to The Bill asking her to write for them. On the cop soap, she says, she learned discipline; the art of telling a complete story in half an hour. Writing for established characters was also the perfect training ground for a young writer.

Running her two careers in tandem, Mickery went on to write and perform in, among other things, Heartbeat, before eventually giving up acting. “As an actor,” she says, “you’re playing everyone’s parts in your head anyway, and writing is just the next stage, isn’t it? You know what a script looks like and you know about tension, so you already have an advantage. I used – some might say abused – a lot of contacts I’d made, sending absolutely terrible scripts to script editors who read them and gave me feedback.”

She adapted the first of the Inspector Lynley Mysteries for BBC1, along with thrillers The Ice House and The Beggar Bride. She describes working on these as “a whole other learning curve”. Her particular flair lies in creating characters you care about and stories that pull you along, almost magnetically. She’s an attractive personality, too: very clever, witty, and slightly conspiratorial. The daughter of a vicar, she says she was acquainted with death at an early age, and maintains that her Yorkshire upbringing may have some bearing on her attitude to death. “I think they’re very realistic about death. It’s not that they’re hardened to it, but in difficult times, they maintain a sense of humour. After all, funerals can be very funny.”

Mickery says that she sees the possibilities of murder in various places, “but that isn’t to say I have a ghoulish or depressed outlook on life.” She recalls growing up in Pudsey where, “in the winter, they used to put wooden floorboards over the swimming pool and convert it into a dance hall. There was always a terrible moment when you realised you were dancing too energetically at what you knew to be the deep end and you’d think, ‘Any minute now, I’m going to plummet to my death.’ ” Suddenly, it all becomes clear.

The latest instalment of Messiah is the last Mickery says she’ll write. She’s turning her attention to, among other things, a drama about the marines and a romance. Mickery catches herself and smiles. “Though when you switch from Messiah to the romance, you do have to remind yourself not to kill anyone in the first five minutes.” When you’ve had as much practice as Mickery, murder is a hard habit to break. Breaking hearts should be a breeze. [Gareth McLean]

Messiah III: Death Pays All Debts, BBC1, August 30 and 31; Dirty War is on BBC2 in October.

Broadcast

Behind the Scenes

Paradox, BBC1, 12 November, 2009

Commissioned surprisingly quickly, the Paradox team had just months to deliver a series. But they relished the challenge, says Clerkenwell Films CEO Murray Ferguson.

Fact File:

PARADOX

• Production company Clerkenwell Films for BBC Northern Ireland

• TX Tuesday 24 November, 9pm, BBC1

• Directors Simon Cellan Jones, Omar Madha

• Writers Lizzie Mickery (creator), Mark Greig

• Producer Marcus Wilson

• Executive producers Murray Ferguson, Patrick Spence

• Stars Tamzin Outhwaite, Emun Elliott, Mark Bonnar, Chike Okonkwo

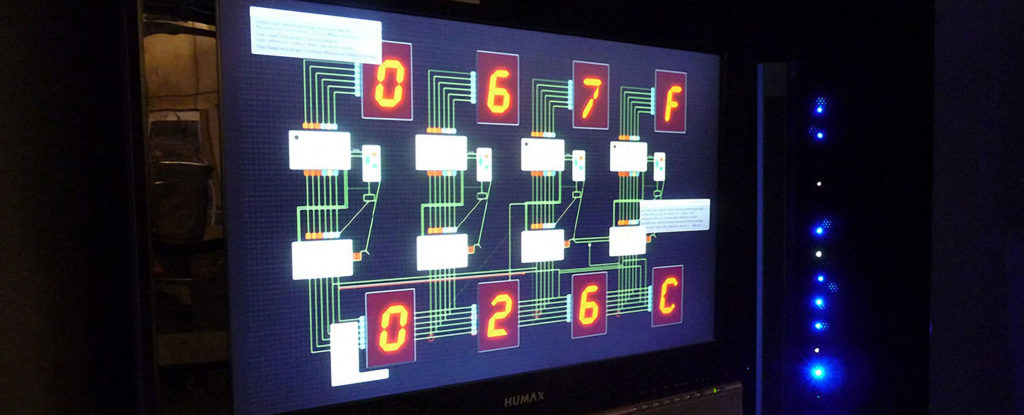

• Summary Fast-paced character-driven thriller. A series of rogue images are transmitted from space, appearing to depict a major incident. Shockingly, they also suggest it is yet to happen.

It’s not often that after you’ve just handed in a script for a drama pilot you get a phone call from the BBC, asking if you can deliver the completed series ready for transmission in nine months’ time. But it is the sort of call you dream of, particularly when new commissions hardly grow on trees these days. It certainly focuses the mind. Add to the mix a second call three weeks later from Channel 4 asking you to pull forward delivery of Misfi ts, our then recently commissioned new series for E4, by 12 months, and suddenly 2009 takes on a new and rather exciting perspective. With one show shooting in Manchester and the other in and around London, travel plans for the year were clearly going to revolve around Virgin trains rather than any long-haul holiday destinations. A welcome trade-off.

Paradox had a very fast turnaround from the outset. Rather than disappearing into any sort of development hell, it moved through the BBC at a rate of knots. At Clerkenwell Films we prefer to develop our projects in a targeted way. We knew there was an appetite at the BBC for a big, bold new show with ambition and scale. Something that would grab an audience from the off and hold onto them until the final frame. We had always been keen to develop a series that incorporated the race against time element that was to become so central to the premise of Paradox, and to combine that with a mystery that could background a whole series and the stories of the week.

With those ideas in mind we approached writer Lizzie Mickery at a very early stage – and she came up with the world we now recognise as Paradox. She did masses of research into space science and satellite systems and at a later date we brought in Dr Maggie Aderin, a world-renowned space scientist, who responded to Lizzie’s ideas and, rather than drowning us in dry theory, proceeded to open our minds to some even more exciting possibilities. Lizzie’s proposals for the characters and stories followed and we went to Patrick Spence at BBC Northern Ireland with the proposal. Both he and [BBC head of drama commissioning] Ben Stephenson loved the ambition of the project and commissioned two scripts. A series commission followed. One of the first absolutely key decisions for me was to find a producer who was clearly excited by the challenges of the show, who was creatively in sync with them and understood what we were all setting out to achieve – and who could then execute this ambition on the usual tight budget and schedule. It needed someone with enormous confidence, courage, sensitivity and production know-how. In Marcus Wilson we found someone with all those qualities.

We also needed a director with flair, energy and passion: someone with the confidence to deliver visually arresting material, who had affi nity with actors and the ability to tell complex and pacey stories with clarity. We had been drawn by the integrity of Simon Cellan Jones’ work over the years and his brilliance on Generation Kill. Setting up a series would be a new challenge for him and something he was eager to embrace.

Paradox always pushed at the limits. By its very nature it needed to do so but it required a strong and experienced team. One of the reasons we chose to film in Manchester was the availability of quality crew. It was my first time filming in Manchester and I was not disappointed.

The series proved very demanding in terms of the time and the money we had. There was at least one massive set up or action sequence in each episode and sometimes two. In an average hour of series drama you might expect to have around 90 to 100 scenes. Paradox has more like 135 to 150. Shooting two cameras continuously certainly helped, but no day was ever straightforward. Ivan Strasburg behind the lens was an advantage. You don’t get much better than him.

Nine months on we are now completing post-production of the two series having weathered some unusual curveballs along the way. The trails are playing, the reaction seems good but you can never completely tell. Maybe this is the time to take that long-haul flight. All will become clear soon enough.

My tricks of the trade:

■ Be considered. Be clear. Be calm, particularly when others aren’t. If it’s not working in the script don’t expect it to work on screen.

■ Put together a great team who share a creative ambition. Delegate and let them do their jobs. Watch the detail but keep your eye on the bigger picture.

■ Do something very different when you have time to clear your head. Cycling. Yoga. Whatever floats your boat.

DIRECTOR’S TAKE

Simon Cellan Jones – Lead director

I wanted Paradox to be shot in a simple, aggressive and slightly unsettling way. I usually shoot hand-held anyway, and this time I wanted the camera to be immersed in the action, ready to react to the actors. I’d shot on two cameras for the first time on Generation Kill, and we did the same on this shoot, which gave us loads more coverage and kept the actors fresh. It was the first time I have used digital, and we shot on the Red One camera. It had its problems but, on the plus side, most of the images looked stunning, with deep blacks, strong colours and a beautiful 35mm feel.

Marcus [Wilson, producer] found some money for a proper Wescam helicopter shot. By some miracle Manchester gave us the most beautiful summer evening light on the day of the shoot, and this gave us a chance to show our locations from the air, giving a strange sense of being overlooked from the heavens.

We had a fantastic set. Matt Gant, the designer, and I spent many hours trying to get a look that was modern and full of deep angles, but functional and authentic-looking. Christian, the strange space scientist who seems to know much more than he is letting on, had a real empire to inhabit, and the set added great depth to his character.

Though Paradox has a police procedural element to it, I was very keen to move away from this genre. And I also wanted to keep away from the sci-fi feel. The idea was that, despite the high concept premise of images being sent from the future, the show’s world was grounded in reality. I wanted the audience to feel this stuff was happening to them. It was important that the images were visceral and frightening – though they came from the future we wanted the sense that, in a few hours’ time, they would become horribly real.

www.telegraph.co.uk, Saturday 08 June 2013

The state we’re in

By Lizzie Mickery and Dan Percival

12:01AM BST 15 Oct 2006

When the writers Lizzie Mickery and Dan Percival needed a convincing backdrop for a conspiracy thriller steeped in fear, they found all they needed at the British Embassy in Washington. If the most prestigious invitation in Washington DC is to the White House, the second is to 3100 Massachusetts Avenue. Here, set discreetly behind wrought iron gates and a port-cochère, stands the British Residence – the Queen’s personal palace in America. To walk through its elegant Lutyens corridors and sumptuous ballroom is a humbling experience. Which is exactly how it’s meant to make you feel. As Sir David Manning, the current British Ambassador and temporary chief tenant, told us with a sweep of his arm, ‘All this is theatre.’

How we came to be in the British Residence in Washington requires a rewind. We were there not as politicians or diplomats but as writers, researching a new drama for the BBC called The State Within set in the British Embassy.

What happens when your views are not those of your masters? In The State Within our fictitious ambassador, Sir Mark Brydon, played by Jason Isaacs, finds himself emotionally and morally torn. He’s already haunted by a decision he made years ago for the sake of political expediency which led to the suffering of innocent people. As the story of explosive events, espionage and the race to prevent a war unfolds, we also set out to look at the personal cost not just to Sir Mark but to all our characters: the intimate human consequences of the ‘bigger picture’, with all the pain, love and betrayal of friendship and family that suggests.

Our last collaboration was the fact-based, terrorist drama Dirty War, screened by the BBC in 2004. While making that film, we became intimately involved in the murky world of political decision-making and intelligence. Two themes became very clear to us as we worked. One was the manipulative power of fear. The other was that ill-conceived policy, however noble the motive, can have appalling consequences. Now, two years on, we wanted to cut loose from the restraints of journalistic accuracy and let our imaginations fly. Our ambition for The State Within was to write a complex, contemporary, conspiracy thriller that paralleled current events.

Fear pulsates throughout the six hour-long episodes of The State Within. George Orwell brilliantly exposed the ways in which fear of an unknown, unseen enemy allows truth itself to be distorted. He used fiction to warn us that the control of information is central to the abuse of power. We do not live in the totalitarian dystopia that Orwell imagined but we have, none the less, entered an age where fear is rife and the manipulation of information is essential to selling policy to voters. But to what extent are our leaders themselves also victims of misleading information? To what degree are they, too, being manipulated by their fears? And how much do they want to believe what they are told in order to pursue their own agenda?

This arena of smoke and mirrors is a rich backdrop for a thriller. With The State Within, we have created a story in which the truth is very rarely what it first appears to be and the information we receive is controlled. But the big question is: by whom and why? Fear heightens our deeper prejudices and acts as a smokescreen that can lead us to misjudge situations and to support knee-jerk decisions in disastrous ways. The series opens with a terrorist atrocity – an explosion on an airliner – that quickly escalates into an international crisis. Accusations are levelled, actions against civil liberties taken that set in train a sequence of events that could lead Britain and America into another war.

Without giving away the plot, the apparent causes of the attack are taken at face value by all our protagonists (the full truth takes a further six hours to reveal). But our quickness to judge on face value is precisely what the drama is aiming to undermine. Just when you think you know what is going on, the rug is pulled from under you.

Since 9/11, the world has changed in ways few of us could have predicted. We have become embroiled in two wars. We have seen secret prisons erected, torture, kidnapping and civil surveillance legitimised and the right of trial curtailed. How many of us could accurately define what the ‘War on Terror’ really means, describe its ultimate aim or predict the outcome? We are left reeling from the speed of this change, wondering how we got here, and where we might yet be headed.

Whether one agrees or disagrees with our transatlantic alliance, it’s clear that being a close ally – or indeed a confidant – of the United States is the only chance of having some influence (however small) on the world’s current superpower. One of the trickiest jobs in the diplomatic world must be that of the British Ambassador to Washington.

We wanted to give our thriller as authentic a feel as possible. To do this, the language, agendas, policies, protocols, headlines and events needed to be grounded in reality. This was a daunting prospect. It didn’t matter how well-read we were in transatlantic politics, to bring this series to life we knew we needed a much deeper, more personal insight into how the diplomatic relationship between Britain and America truly functions. And that meant going to Washington.

We were astonished by the positive response that we received from the embassy to our request for a visit. Although the staff had no part in influencing the story that we would write (nor have they read the finished scripts), they offered us a level of access to Washington that ‘newcomer’ journalists and documentary makers would die for. We had meetings with most of the leading Counsellors and First Secretaries, including lunch with the Ambassador, Sir David, and key members of staff in the residence.

Neither of us was certain what lunch entailed. Sandwiches, a quick chat? We were taken towards the drawing-room (Chippendale mirrors and heavily carved giltwood console tables). Despite the fact that there were only seven of us at the table, place names had been written and menus printed. As the butler and valet moved quietly around the table, the conversation was free-ranging and easy. No wonder the Residence is on the A-list of must-have invites in the city – Sir David’s description of it as theatre was not a flippant remark. It not only provides an impressive setting to entertain international dignitaries and host grand events, but also projects the confidence and maturity of a great power that has earned the right to play a central role in global affairs.

But the real secret to maintaining Britain’s place on the international stage lies in the drab, red-brick Sixties office block next door. In contrast to the splendour of the Residence, the grim, municipal exterior of the British Embassy would look at home in any English town centre. But what it houses is none the less impressive. Otherwise known as ‘Whitehall on the Potomac’ (every government department is represented inside), the Washington embassy, and the diplomatic minds it contains, are devoted to the primary goal of staying one step ahead of the game. Or, as one high-ranking Counsellor put it, ‘To anticipate what the US administration is going to do, before it knows itself’. We were told many times that there is no such thing as a ‘special relationship’ – nothing, at least, that can be taken for granted.

The skill of the British Embassy staff at inveigling themselves into every important nook of Washington is legendary. The British Embassy is one of only a few that have their own lobbyists on Capitol Hill working on behalf of British interests. Officials in the US State Department expressed, with some awe, how their counterparts in the British Embassy were on first-name terms with people they called ‘Sir’. They even admitted that if they wanted to know what was going on inside their own vast departments and government agencies, they would often be better off asking their contact at the embassy.

As several Counsellors we met pointed out, the art of diplomacy is the prevention of war. There is a constant pressure to anticipate conflict and defuse it, often in tinderbox situations. If a situation does flare up, they have to work against the clock to resolve it. Lives can be at stake. It was in this fragile arena of internal and external tensions, where wrong choices can lead to catastrophic results, that we wanted to set our thriller.

To be a top diplomat requires guile, charm and the ability to earn trust. It also requires the public suppression of personal opinion. In The State Within, as Sir Mark crosses swords with the British and American governments, there is an intense inner conflict between Mark the ambassador and Mark the man.

One thing our trip taught us is that the actions of governments or individuals in power are never black or white, good or evil. As one White House CIA analyst (who will have to remain nameless) explained, decisions are more often than not made in what is believed to be the best interests of the American people. Never underestimate the sincerely held view that what is good for America is good for the rest of the world (however misguided that may be). Too often, the bad consequences result from a headlong rush to ‘do good’. And when our leaders make decisions that seem disastrous, it may well have been the lesser of two evils. The right thing to do is very often not the best thing to do.

It’s this nebulous, grey world that makes a fertile breeding ground for international conspiracy, a grubby environment that feeds an army of private military contractors, lobbyists, the disillusioned, the opportunists – the service industry of human strife.

This, for us, is The State Within, the place deep in the heart of global decision-making where right can be wrong, black can be white and the truth is far more complex and ambiguous than it might first appear. Our ambassador, Sir Mark Brydon, goes on a dangerous and deadly journey until he is ultimately confronted by an almost impossible dilemma. At what point do you sacrifice the truth for the sake of your country? At what point do you sacrifice your country for the sake of the truth? In The State Within, nothing is what it first appears.

Jason Isaacs on playing the British Ambassador:

You made your name playing ‘bad guys’, like Lucius Malfoy in ‘Harry Potter’ and the inherently evil Colonel Tavington in ‘The Patriot’. How much bad is there in Sir Mark Brydon?

Villains are often much more interesting to play than heroes because the well-written ones have some serious character flaws to chomp your acting teeth into. From my point of view (maybe for my own selfish desires) the challenge with a traditional hero such as Mark was to create a flawed character who struggles between doing the right thing morally, personally and professionally, and who changes from the beginning of the story to the end. Luckily the writers, Lizzie Mickery and Dan Percival, agreed and we created a backstory in which Mark has made some very questionable decisions protecting British interests abroad and the chickens come home to roost during our story. Has he been good, bad or pragmatic? You decide.

Did you prepare for the role by reading Sir Christopher Meyer’s book ‘DC Confidential’? Or are you not that sort of ambassador?

Dan and Lizzie spent time in Washington with Sir David Manning (the current ambassador) and his staff and were not only fonts of wisdom but also gave me the transcripts of all their interviews. The BBC made their documentary archive available, which had some classic diplomatic and fashion disasters to emulate and avoid, and I read Sir Christopher’s book. Mostly, though, since we were creating an ambassador who was enough of a maverick to have ruffled feathers all along, I locked myself in a room with Dan and Lizzie and we played ‘what if’. What if the ambassador wasn’t the public school Oxbridge graduate we expect? What if he was a close friend of the PM? What if, when our story begins, he was about to enter politics proper? On a more superficial note, I got the braces idea from Sir Christopher’s habit of wearing red socks all the time and Michael Grade’s famous braces. Only halfway through shooting did I find out that everyone hated them – but by then it was too late!

You play a British ambassador striving to save the world from terrorist attack. Isn’t that a bit unrealistic? Apart from everything else, Blair emasculated the Foreign Office years ago…

An ambassador, in the words of Henry Wooton, ‘is an honest man sent abroad to lie for his country’. His job, traditionally, is simple: to prevent war. It might be argued that that has changed over the past five years, given the recent doctrine of the pre-emptive strike, but mostly they are there to quell fears, calm misunderstandings and whisper in ears. Reading Sir Christopher’s memoirs of his time in Washington during the decision to go to war with Iraq was a real eye-opener into just how influential these unelected representatives are: whom they know, who takes their call – who trusts them can have a massive effect on international relations. On top of all that, Mark Brydon’s a maverick anyway: everyone – literally all the parties, including the oppressed population – stands to gain from the invasion and regime change that the world hurtles towards in the story, but Mark smells a rat and he’s reached a stage in his life and career when one more cover-up might be one too many. What’s unusual in the script – and for me as an actor – is that he has to solve these problems with diplomacy, manipulation, guile and not a gun, a bag of money and a horse.

Isn’t your character too dashing to have gone through the hard grind of the Civil Service?

You’ve obviously never spent any time with diplomatic high-fliers. These men and women have to be fabulously charming, utterly adaptable and, for good measure, completely ruthless. Their entire career rests on their ability to prise pieces of information from their mute counterparts while giving nothing away themselves. Apart from which, a good number of them are actual spies, and you don’t get more dashing than that.

What did you and the scriptwriters do in August when life started imitating art during the British airport security alert?

I don’t think there was ever any doubt that The State Within deals with things that are and would be in the news. That’s the territory of our factual life and where better to explore our responses than through fiction? Although our story starts with an explosion set off by a British Muslim and the ramifications in Washington, it quickly becomes a conspiracy thriller set on the world stage. As people die around me and there’s a rush to war, it’s down to the ambassador to unravel the truth. Much the same could be said for all of us: if the show contains any message at all it’s to examine what we’re told carefully, work out what must, self-evidently, be true and who has what to gain from what. Hopefully, and in an entertaining way, the story brings us face-to-face with the impossible job of reconciling the need to tell the truth to the electorate, protect our commercial and strategic assets and do the right thing. Something’s always got to give. The Prime Minister got it right recently… I wouldn’t want his job.

Interview by Alastair Smart

The Stage

Messiah writer Mickery pens new ITV crime drama

Messiah writer Lizzie Mickery has created a new drama for ITV1 entitled Instinct. The show follows DCI Thomas Flynn – played by Anthony Flanagan from Shameless, Vincent and the new Cracker – as a brusque cop with a troubled personal life, who has to find a serial killer stalking the quiet of rural Lancashire.

Instinct is produced by Tightrope, the award winning, independent production company founded by Shameless creator Paul Abbott and renowned producer Hilary Bevan-Jones, the new chair of Bafta and an Emmy award winner for The Girl in the Cafe. It will be filmed in and around the Rossendale Valley, in the Lancashire Pennines.

Executive producer Bevan-Jones said “Lizzie Mickery has devised a riveting plot set against the atmospheric backdrop of the Rossendale valley. Viewers will be second guessing until the final moments of the drama.”

Silent Witness’ Tom Ward, Claire Hackett, Michael Hodgson and Christine Bottomley also star in the two-parter due to be screened on ITV1 in early 2007.

Paradox is a bold, fast-paced, character-driven thriller from Clerkenwell Films for BBC Northern Ireland. This gripping five-part series for BBC1 stars Tamzin Outhwaite (The Fixer, Hotel Babylon) as Detective Inspector Rebecca Flint, who is thrown together with Space Scientist Dr Christian King when a series of rogue images are transmitted from space into his laboratory. The fragmented images appear to be of a major incident but, shockingly, they also suggest it is yet to happen.

With each episode of this high-concept and intriguing series set to a relentless ticking clock, Christian, Rebecca and her team, DS Ben Holt (Mark Bonnar) and DC Callum Gada (Chiké Okonkwo), face a race against time as they only have eighteen hours to put together the clues of this most complex of jigsaw puzzles and try to prevent almost certain tragedy. The reason how, and why, these images are being transmitted to them is a mystery. Forced to intervene in the course of destiny, the underlying question posed throughout Paradox is: ‘If you could see the future, would you change it?’ Created and written by Lizzie Mickery (Messiah, The 39 Steps and The State Within), presumably before she’d heard what FlashForward was going to be about, Paradox is directed by Bafta award-winning Simon Cellan Jones (Generation Kill, Our Friends In The North) and Omah Madha (Law & Order: UK, Burn Up) and commissioned by Ben Stephenson and Jay Hunt. That one sounds pretty decent. [Liz Thomas]

The Guardian

Faith, soap and charity

Wednesday 27 March 2002 02.24 GMT

Comfort was in short supply in Sinners (BBC1), Lizzie Mickery’s drama about the “fallen” women who worked in Ireland’s Magdalen laundries. This wasn’t because it harked back to the days before fabric softener (although it was, being set in 1963) but because it was an unusually brave and bleak piece of television.

From the outset, Anne-Marie Duff’s central performance gave Sinners a beating, bleeding heart. As she was renamed Theresa, shorn of her hair, dressed in a regulation smock and told “you’re not supposed to ask personal questions”, the erasure of her identity – as a prelude to the removal of her baby – was as forceful as her determination to hold on to her sense of self. From a naive country girl who trusts the system to a resistance fighter, Theresa’s growing fierceness was both exhilarating and depressing to watch. That it was matched by the purse-lipped zeal of Sister Bernadette (Tina Kellegher) made it all the more mesmerising.

With vindictive nuns, sleazy priests and put-upon but plucky women, Sinners could have tipped over into a festival of stereotypes. It did occasionally teeter but there was, thankfully, no moment of experimental lesbianism under the starched sheets in the wee small hours. Instead, it slowly revealed the collusion of the state in the incarceration of the “Maggies”, and the extent to which the Catholic Church perverted Christianity in its barbarism – but never once became didactic. The stories of Theresa, Kitty (a superlative Bronagh Gallagher) and their fellow prisoners were always the focus of the drama, which used the pop music of the time to achieve a thoroughly anti-Heartbeat effect. Never before has Cilla singing “Anyone who had a heart” had quite such bitter resonance.

It looked fantastic too; Sinners’ world was one of washed-out blues, greys and browns, of grimy outbuildings and darkened rooms in which nuns pecked and clawed at the Maggies like malevolent ravens. It’s hard for us to comprehend the fear and control that women like those in the laundries – and the single mothers committed to psychiatric hospitals in the UK – were subject to, never mind the madness that compels a state to sanction it, but Sinners brought that understanding a little closer.

Not that there was anything radical about the story. The tale of a young woman removed from her family and forced to endure humiliation and brutality and to see her hopes dashed, only to emerge a stronger human being, is the stuff of fairy tales. Similarly, there was little nuance in the writing – morally, it was black and white, with nurse Nuala showing The System’s only humanity – though it wasn’t without its poetry. “Never trust a woman who can add up quicker than you. That’s what my Da’ used to say,” said the man who would later betray Kitty. His sentiments seemed to sum up the idea behind the Magdalen laundries, themselves a symbol of how religious fundamentalists try to control women.

Refreshingly unsentimental, Sinners’ penultimate scene may have been of Theresa, having reclaimed her real name, walking through the gates of the laundry but its last image was of the hellish place – and the poor women – she had left behind. Even her emancipation was double-edged as she had managed it only with the consent of two men. Sinners thus had an integrity about it while satisfying the audience’s need for some sort of upbeat resolution.

That such a drama was on BBC1 in prime time was also unusual. Chastised for its reliance on lightweight, unimaginative and soap star-led drama, Sinners, from the increasingly prolific BBC Northern Ireland, lent the channel some badly needed credibility, not to mention a shot at winning best single drama at next year’s Baftas. (Which was perhaps the intention all along, he added cynically.) If only BBC1 had had a little more tact and treated the clever and crafted Sinners with respect rather than have it straddling the news in a wholly undignified manner, you could believe they had faith in clever, challenging and mature television drama.

“I am a spokesman of God in showing the beauty of ourselves,” said Professor Gunther von Hagens in The Anatomists (Channel 4). Infamous for his “plastinated” corpses, it is a claim he can make with more legitimacy than those who defend the institutions which begat the brutality misogyny depicted in Sinners. Immortalise that in polymers, why don’t you. [Gareth McLean]